My writing living: Sarah Woods, Tinniswood Award Winner 2018

In the first interview in a new series inspired by the latest ALCS research into author incomes, the 2018 winner of the ALCS-sponsored Tinniswood Award tells Caroline Sanderson how she earns a living by working only on projects she really believes in.

When we speak on the phone, Sarah Woods is coming to the end of a busy week at the National School for Performing Arts in Denmark, where she periodically teaches playwriting students. Describing herself as a writer and activist, her 30-year writing career has encompassed theatre for both adults and children, opera libretti, television screenplays, original drama and adaptations of classics for radio, as well as teaching and campaigning work. “I’ve been writing since I left school,” she tells me. “I didn’t do a degree – I thought I’d just give myself a few years to see how it went…..and it went well. I did part of David Edgar’s MA in Playwriting, as it then was, but otherwise, I’m lacking in formal qualifications and have just worked in practice.”

Whilst her CV is strikingly varied in terms of the settings she has worked in, there is a unifying theme. “I work with story across a wide spectrum. I write commission-based work for radio and for theatre, and opera, and I’ve done some TV. Then there’s my community-based work.” Woods has recently written an opera libretto, Wake, for the Birmingham Opera Company, which will pair a professional orchestra and soloists with a big community cast when it premieres in March. She also works with theatre company, Cardboard Citizens, a leading practitioner of forum theatre, which works with people who have experience of homelessness, or who are at risk of becoming homeless and with other community initiatives including London Bubble.

“I found myself a single parent with three children, pretty much solely financially supporting all of them, both at home and at university. So I looked at what I needed to earn and I set myself a target.”

In terms of her activism, Woods, who is based in Hertfordshire, contributes to various campaigns, working with organisations such as the Fabian Society and the Centre for Alternative Technology on film-making and community engagement. She is also a member of a think tank called The New Weather Institute which combines creativity with campaigning. “I always ask myself: how can I be most useful in creating the changes I feel we need to see in the world? Then I’ll use whatever I can in my writing toolkit to help me do it. This gives me a really healthy spectrum of work where I’m often out in the world, working with marginalised groups, with experts, with people who are the top of their field, and also with students. I do a range of things which I really enjoy and which release me from some of the limits of writing commissions. But I only do work that I feel is useful in the world and that I absolutely believe in.” Woods’ unwillingness to compromise her sense of purpose as a writer has led to her turning down potentially lucrative commissions for television. “Perhaps it would have been an easier route. But I’ve done some TV and I found it completely took me over and I didn’t feel good about myself.”

How has she has balanced these strong creative and campaigning principles, with the need to earn a living? “I found myself a single parent with three children, pretty much solely financially supporting all of them, both at home and at university. So I looked at what I needed to earn and I set myself a target.” Woods realised that she had to create a market for the work she wanted to do. “A playwright working in campaigning isn’t a common thing, so I used my skills to crack open spaces for myself and also to develop my teaching. I view my career as a system, where I’ve tried to ensure as many interconnections between the different elements as possible. And I also work really hard!”.

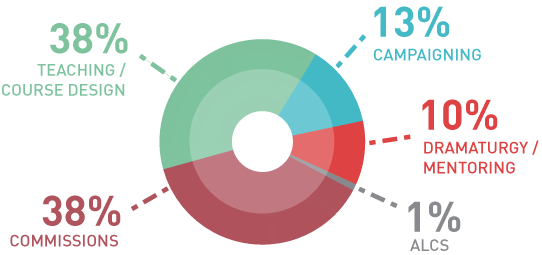

In supplying figures for the income pie chart below, Woods comments that, for it to be truly representative, it would need to plot time as well as money. “I know that I spend much longer on the commissioned work per £1 earned than I do on my teaching. Commissions may make up 38% of my income, but I imagine they take up nearer 60 or even 70% of my time. So, contrary to what you might imagine, my teaching and campaign work subsidise, for example, my BBC commissions.”

Sarah’s income sources during 2016/17

The considerable skills we build up as self-employed writers are not to be underestimated in terms of pitching for work, Woods believes. “This is something I talk to my students about, especially third years who are about to go into the world thinking they’ve been trained only for very specific things. I say, yes, we’ve learned to write a play or perform and direct a play, but we’ve also learned to collaborate closely with other people, to problem-solve. And certainly as playwrights, we learn to work strategically in really complex ways, to think deeply about a variety of different people’s motivations in the world: about what causes conflict and how to manage conflict. For myself, I found that I’d developed a mature set of teaching skills and had a lot to pass on to other people and organisations.”

Perhaps surprisingly, for a writer who has lived with the financial pressures of being a single parent, Woods is also a strong advocate for working without payment on occasion. “I try and have the idea that about a fifth of my time is spent doing things for nothing. That might mean mentoring someone or working for a charitable cause. It’s good to work for no money sometimes. Money is just one of those boring things that we have to have. It’s good to be released from that occasionally. I like the principle of service, by which we offer our skills to people when they’re useful. I like to imagine a world where such principles are part of everyday life, so modelling them in my own way is important. Then again, sometimes I’ll end up in a paid job because of something I’ve done for free.”

“I say, yes, we’ve learned to write a play or perform and direct a play, but we’ve also learned to collaborate closely with other people, to problem-solve.”

Woods dislikes the business of self-promotion, with her input on social media restricted to the occasional post on Facebook (“I actually have no interest in any of it”). For her, networking and self-publicity is much more about building on the relationships she has forged during her career. “While writing often feels like a solitary act, it’s also about our relationships with human beings. The deep collaborations that I’ve had over decades have helped get me through difficult times. When I was under duress, I went round those people who have always supported me and said, look: I really need work now. I don’t think there’s any harm in that.”

What advice would she give to anyone trying to make a living in the fields of playwriting and scriptwriting? “When I look at character with students, I talk about the importance of knowing what their wants and needs are. Perhaps everyone should ask themselves honestly: what are my wants and needs as a writer? For me, writing is an integral part of myself and my relationship with the world. It’s how I naturally communicate, not just a way to earn money. For some people, making a living might mean carving out one or two days for writing among other activities. I think it’s important to protect the thing you love, and therefore to pause for thought before leaping into any arena purely in order to make a living.”

Sarah Woods writes across all media, including theatre, radio and opera. Her work has been produced by numerous companies, including the RSC, Hampstead Theatre, Soho Theatre and the BBC, regional theatre and touring companies, as well as Graham Vick’s Birmingham Opera Company. She is this year’s winner of the prestigious and ALCS-sponsored Tinniswood Award for her BBC Radio 4 drama, Borderland which was described by the judges as a “dark and original dystopia which takes an inspired perspective on issues of migration and identity”.

What are words worth in 2018?

We have launched a major survey into the earnings of authors in all genres, the third such piece of research in the past decade, and urge all ALCS members to participate by the closing date of 28 February. Results from 2014’s What Are Words Worth Now? found that the median income of professional authors had fallen from £15,450 in 2005 to £11,000 in 2013. In addition, the number of authors earning a living solely from their writing had dropped from 40% in 2005, to 11.5% by 2013.

Such data is vital in enabling ALCS to continue to make the case for fair terms for authors in copyright law, licences and contracts. So we urge all members to please complete this latest survey so that we can continue to protect and promote your rights effectively.